Key Reasons Founding CTOs Move Sideways in Tech Startups

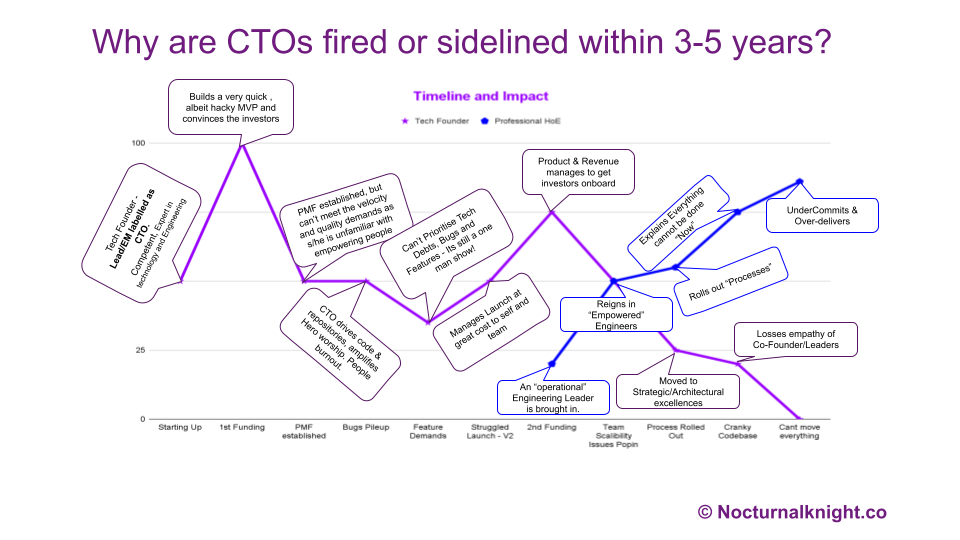

In the world of startups, it’s not uncommon to hear about founding CTOs being ousted or sidelined within a few years of the company’s inception. For many, this seems paradoxical—after all, these are often individuals who are not only experts in their fields but also the technical visionaries who brought the company to life. Yet, within 3–5 years, many of them find themselves either pushed out of their executive roles or relegated to a more visionary or peripheral position in the organization.

But why does this happen?

The Curious Case of the Founding CTO

About 6-7 years back, while assisting a couple of VC firms in performing technical due diligence with their investments, I noticed a pattern: founding CTOs who had built groundbreaking technology and secured millions in funding were being removed from their positions. These were not just “any” technologists—they were often world-class experts, with pedigrees from prestigious institutions like Cambridge, Stanford, Oxford, MIT, IIT(Israel) and IIT (India). Their technical competence was beyond question, so what was causing this rapid turnover?

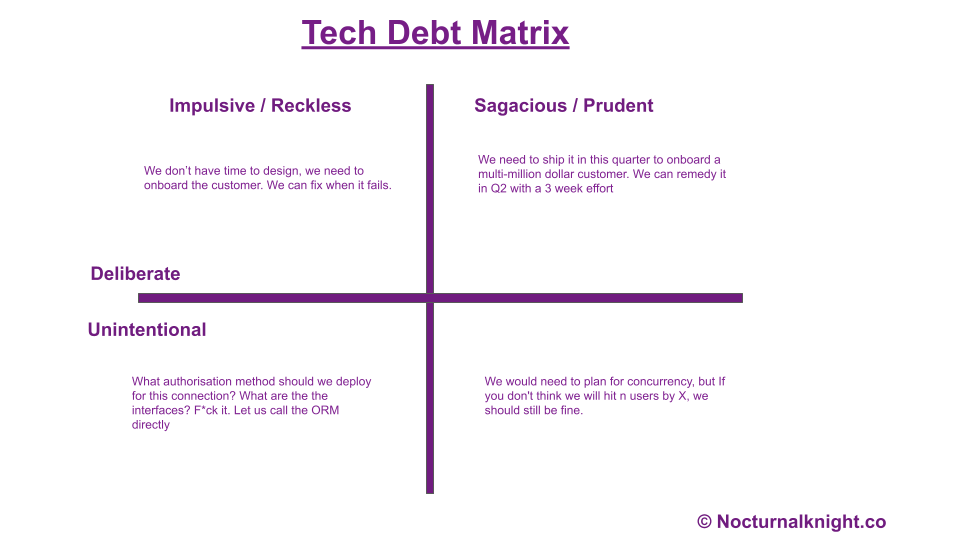

The Business Acumen Gap

After numerous conversations with both the displaced CTOs and the investors who backed their companies, a common theme emerged: there was a significant gap in business acumen between the CTOs and the boards of directors. As the companies grew, this gap widened, eventually becoming a chasm too large to bridge.

The Perception of Arrogance

One of the most frequently cited issues was the perception of arrogance. Many founding CTOs, steeped in deep technical knowledge, would often express disdain or impatience towards board members and executive leadership team (ELT) members who lacked a technical background. This disdain often manifested in meetings, where CTOs would engage in “geek speak,” using highly technical language that alienated non-technical stakeholders. This attitude can make the board feel undervalued and disconnected from the technology’s impact on the business, leading to friction between the CTO and other executives.

Failure to Translate Technology into Business Outcomes

Another critical issue was the inability—or unwillingness—to translate technical initiatives into tangible business outcomes. CTOs would present technology roadmaps without tying them to the company’s broader business objectives; and in extreme cases, even product roadmaps! This disconnect led to frustration among board members who wanted to understand how technology investments would drive revenue, reduce costs, or create competitive advantages. According to an article in Harvard Business Review, this lack of alignment between technical leadership and business strategy often results in a loss of confidence from investors & executive leadership who see the CTO as out of sync with the company’s growth trajectory.

Lack of Proactive Communication and Risk Management

Founding CTOs were also often criticized for failing to communicate proactively. When projects fell behind schedule or technical challenges arose, many CTOs would either remain silent or offer vague assurances such as, “You have to trust me.” Sometimes, they fail to communicate the underlying problems causing this. This lack of transparency and the absence of a clear, proactive plan to mitigate risks eroded the board’s confidence in their leadership. As noted by TechCrunch, this lack of foresight and communication can lead to the CTO being perceived as “dead weight” on the cap table, ultimately leading to their removal or sidelining.

The Statistics Behind the Trend

Research supports the observation that founding CTOs often struggle to maintain their roles as companies scale. According to a study by Harvard Business Review, more than 50% of founding CTOs in high-growth startups are replaced within the first 5 years. The reasons cited align with the issues mentioned above—poor communication, lack of business alignment, and a failure to scale leadership skills as the company grows.

Additionally, a survey by the Startup Leadership Journal revealed that 70% of venture capitalists have replaced a founding CTO at least once in their careers. This statistic underscores the importance of not only possessing technical expertise but also developing the necessary business acumen to maintain a leadership role in a rapidly growing company.

Real-World Examples: CTOs Who Fell from Grace

Several high-profile cases illustrate this trend. For instance, at Uber, founding CTO Oscar Salazar eventually took a step back from his leadership role as the company’s growth demanded a different set of skills. Similarly, at Twitter, co-founder and CTO Noah Glass was famously sidelined during the company’s early years, despite his pivotal role in its creation.

In another notable case, at Zenefits, founding CTO Laks Srini was moved to a less central role as the company faced regulatory challenges and rapid growth. The decision to shift his role was driven by the need for a leadership team that could navigate the complexities of a scaling business.

And, the list is too long, so I am adding about 8 names which is bound to elicit a reaction.

| Name | Company | Fired/Left on Year | Most Likely Reason |

| Scott Forstall | Apple | 2012 | Abrasive management style and failure of Apple Maps |

| Kevin Lynch | Adobe | 2013 | Contention over Flash technology, departure to join Apple |

| Tony Fadell | Apple | 2008 | Internal conflicts over strategic directions |

| Amit Singhal | Google/Uber | 2017 | Dismissed from Uber due to harassment allegations |

| Balaji Srinivasan | Coinbase | 2019 | Strategic shifts away from decentralization |

| Alex Stamos | 2018 | Disagreements over handling misinformation and security issues | |

| Michael Abbott | 2011 | Executive reshuffle during strategic redirection | |

| Shiva Rajaraman | WeWork | 2018 | Departure during company instability and failed IPO |

The Path Forward for Aspiring CTOs

For current and aspiring CTOs, the lessons are clear: technical expertise is essential, but it must be complemented by strong business acumen, communication skills, and a proactive approach to leadership. As a company scales, so too must the CTO’s ability to align technology with business objectives, communicate effectively with non-technical stakeholders, and manage both risks and expectations.

CTOs who can bridge the gap between technology and business are far more likely to maintain their executive roles and continue to drive their companies forward. For those who fail to adapt, the fate of being sidelined or replaced is an all-too-common outcome.

Conclusion

The role of the CTO is critical, especially in the early stages of a startup. However, as the company grows, the demands on the CTO evolve. Those who can develop the necessary business acumen, communicate effectively with a diverse range of stakeholders, and maintain a strategic focus will thrive. For others, the writing may be on the wall well before the 3–5 year mark.

What other reasons have you found that got the founding CTO fired? Share your thoughts in the comments.

References: & Further Reading

- Harvard Business Review: Unpacking VCs’ Strange Instinct .

- Adeline Chalmers on Medium: Without Business Acumen, Most CTOs in Scaleups Will Be Replaced in Time .

- TechCrunch: Bad CTOs Mean Startups Have Millions Worth of Cap Table Dead Weight .